If, like me, you grew up in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s it’s likely that Ron Gilbert is responsible for many of your formative gaming experiences. While at LucasArts he was responsible for a red-hot run of bona fide adventure game classics, including Maniac Mansion, Zak McKraken and the beloved Monkey Island series.

In January, he returns to the fray with The Cave, a delightful Sega-published 2D romp that, in true Maniac Mansion tradition, sees you picking three characters from a wildly diverse line-up of seven oddballs and descending into the titular caverns for all manner of puzzle-centric adventure.

From the brief section we’ve played, it’s clear that Gilbert has lost none of his flair for fiendish puzzle design, barmy dialogue and madcap storytelling. It’s shaping up to be a charming, challenging and wonderfully eccentric title that will both delight his core fans while being accessible enough to win plenty of new ones.

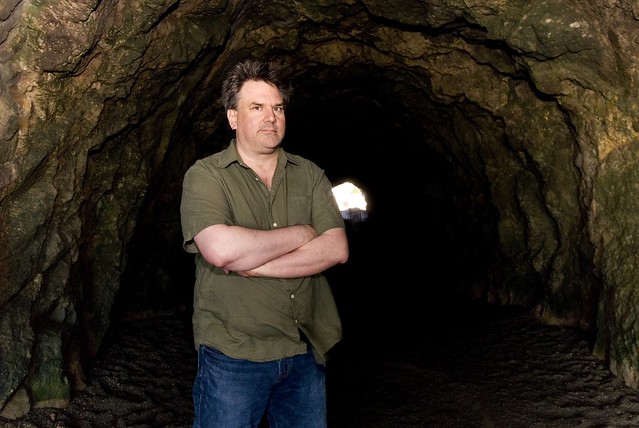

We caught up with the man himself when he was in London earlier this week to find out a little more about the project.

You’ve said that the concept for The Cave has been in your head for more than 20 years. Why has it taken so long to get it made?

Ron Gilbert: Well, I have a lot of ideas floating around my head. I’d think about The Cave every once in a while and put another piece of the puzzle in place, so to speak. It wasn’t until a couple of years ago when I was having lunch with [Double Fine founder] Tim Schafer that things really started moving.

We were talking about games and The Cave had just popped into my mind. I told him about it and he thought it was a great idea so he said ‘why don’t you come to Double Fine and make it?’ They had a free team at the time so it was just the perfect aligning of two things. It was just random luck.

You’ve spoken a lot recently about how much you enjoyed Limbo. The two games seem to have a few elements in common – was its release a catalyst for pushing The Cave back into your thoughts?

Ron Gilbert: It was a little bit. Playing Limbo was what got me thinking about The Cave again. I played Limbo and I really liked it. It’s a brilliant game. It’s not an adventure game – a lot of people dispute this – but I don’t consider it an adventure game. But it’s a brilliant game nonetheless. And it did kind of start my mind thinking a little bit, and dredged up The Cave. Especially the 2D element – I always imagined The Cave being this 2D ant farm, you know?

What other sources of inspiration have you drawn upon?

Ron Gilbert: A couple of things. The first adventure game I ever played was set in a cave – the original Colossal Cave. It was very inspiring to be able to follow that tradition.

And caves are just inherently interesting and mysterious. We lived in them 40,000 years ago, y’know. There’s just something about them – they’re really ingrained in our brains on some level.

And then the other inspiration was just what Gary [Winnick, LucasArts designer] and I had done with Maniac Mansion, with the seven characters. I’ve always wanted to revisit that formula and this was the perfect vehicle.

Are you much of a spelunker in your spare time?

Ron Gilbert: No, I’m actually somewhat claustrophobic… going into a cave for real creeps me out a little bit.

What would the Ron who made Maniac Mansion back in 1987 think of The Cave?

Ron Gilbert: Where the hell are the verbs?

Do you think it’s markedly different to those classic LucasArts games?

Ron Gilbert: Well, I think at its core The Cave is just a good solid adventure game. If you look at the puzzle structure of Monkey Island and the puzzle structure of The Cave they share a lot in common. But for The Cave, it was just about streamlining – looking at things like inventory and traversal and just trying to re-examine them. In a similar way that Gary and I looked at Maniac Mansion and wanted to get rid of the parser, and just streamline some of that stuff out of those games.

That’s really what The Cave is about. Maybe we’re right about some of it, maybe we’re wrong. Maybe people really do want inventory. You’re just always trying new things and feeling your way through it and making adjustments for the next game.

Does stripping out the inventory make the game more accessible to newcomers?

Ron Gilbert: I think it does, in a way. Gaming has become much more mass-market. A lot of people play games these days – on their phone, or their tablet, or whatever. They’re not necessarily interested in these fast-reaction, hyper-violent games with lots of neck-stabbing or whatever, but they are interested in slower things and they really do like puzzles.

The best-selling game of all time is Angry Birds. And it’s a puzzle game. You use your brain to puzzle things out. But there is this visceralness to it – you watch these birds smash into stuff.

For the larger mass-market, adventure games are probably a really great thing, but maybe they don’t want a bunch of verbs on the screen or to rifle through hundreds of items in an inventory. So it’s just about streamlining stuff away and seeing whether that’s more in line with what a modern gamer is looking for.

You must have designed hundreds of puzzles over the years. How do you keep them fresh?

Ron Gilbert: Puzzles in adventure games are probably a lot like stories. If you look at adventure games you can probably boil every puzzle down to one of, say, 20 puzzles. It’s the same with movies. You could take every single movie plot ever made and boil it down to 25 basic plots. It’s what you put on top of that – the other scenarios, the characters, all of those things.

If you were to deconstruct all the puzzles in the The Cave’s carnival section you probably wouldn’t find anything too original. But the fact that we wrapped them up in this carnival and gave them to you in different orders makes them seem fresh and new. Like with movie plots, it’s how you dress it up that makes it interesting.

Are there any adventure game clichés that you find really difficult to avoid?

Ron Gilbert: The absurdity of it all. It’s one of the reasons I’ve always enjoyed making adventure games that are comedies. At some level, there’s just the absurdity of using weird items in weird ways.

If you’re doing a game that is completely serious it’s always struck me as odd that I’m combining a pencil with some bubblegum to get a coin out of a sewer, while trying to tell a serious hard-boiled detective story. Those things just don’t match.

If you’re doing a comedy you can get away with a lot of that stuff, as people are more willing to accept it. But that absurdity of using strange items to solve puzzles can be a very hard thing to get away from.

What makes a great video game character?

Ron Gilbert: In some ways the same things that make a really good movie protagonist. There’s something about a protagonist that the player needs to be able to relate to. There’s always some kind of challenge they’re trying to overcome – that’s always a cornerstone of any movie.

That works well in games as you as the player actively help the character overcome it. So, protagonists are a little bit about aspiring to more than you actually are. It’s about getting caught in some kind of a problem and trying to work your way out of a problem.

Out of all the characters you’ve created, which one is your favorite?

Ron Gilbert: Probably Guybrush [from Monkey Island]. He’s a bumbler, right? He’s not the smartest person in the world, he really isn’t. He just bumbles his way through. He’s the butt of jokes, but he doesn’t know it. He imagines he’s a much better pirate than he actually is. That’s fun to write for and fun to make puzzles for because you can really play off it without the character themselves turning into a buffoon. I think Guybrush is really special because of that.

Related Posts:

- Ron Gilbert spills more details on The Cave, plans to talk to Disney about Monkey Island rights - GoNintendo

- The Cave - Ron Gilbert video interview - GoNintendo