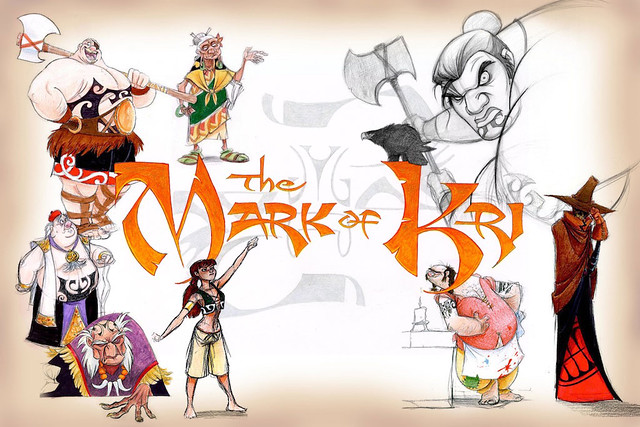

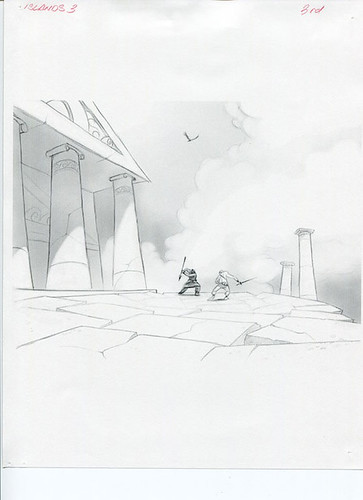

Editor’s Note: Beloved PS2 Classic The Mark of Kri will be available on PS3 via PlayStation Store next Tuesday, so we reached out to the game’s Executive Producer, Jonathan Beard, to ask for some stories and insights from its development. He responded in kind, with one of the most detailed write-ups in PlayStation.Blog history, and a bevy of heretofore unseen concept art. Enjoy.

Click here to see the full gallery

In the early 2000′s, I had taken over the role of studio director at SCEA San Diego, and moved from Foster City with some key members of the Blasto team. Tim Neveu who was the lead artist on Blasto was given the chance to produce his first game. Tim and I had known each other for a while and shared a lot of the same interests. We often discussed classic games and were alligned on the kind of game we wanted to make – a “fantasy” game – big guy and a sword, maybe an axe.

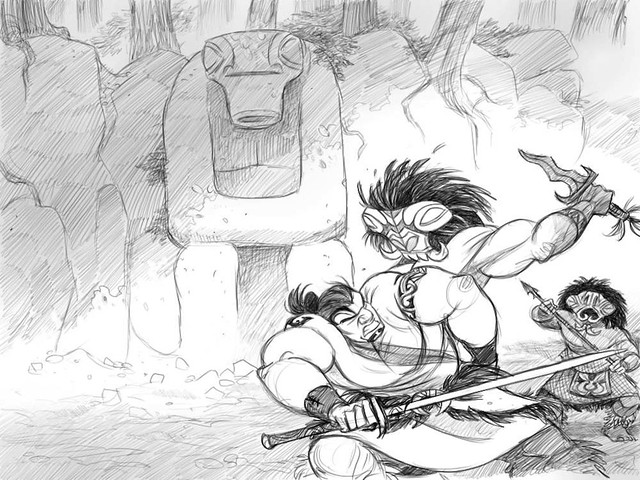

We were both fans of the original C64 “Barbarian” game, and loved how satisfying it was (even on an 8 bit system) to decapitate your foe. We wanted to make a game that had very real reactions to being hit with a heavy peice of sharpened steel. Animated gratuitous violence, and no blue sparkles for blood.

We were big fans of John Milius’ original Conan the Barbarian movie and liked the idea of what we called “plausable fantasy”. This was pre Lord of the Rings trilogy, so Conan was one of the only great fantasy movies – in our opinion everything else was pretty much pure cheese.

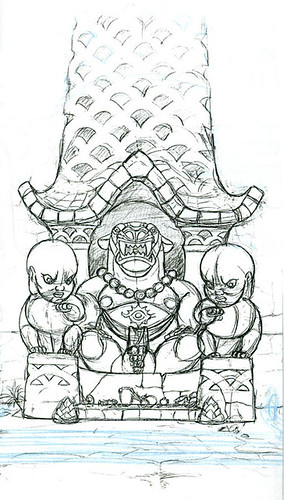

We wanted to make a game in the fantasy genre that didn’t smack of Dungeons and Dragons influences. Something like the original Conan movie – clearly fantasy, but with some plausibility to it. No lizard people, no flaming swords.

These elements were the starting point for The Mark of Kri, or as it was originally called: Barbarian.

Unfortunately, after a year or so of PS1 development the game was struggling. This was in part because we were pushing the limits of the hardware; but there was also something missing – it was like we had a few nice chords, maybe even a riff, but no song…

Around this time, Shuhei took over development at PlayStation and became interested in the game. Despite its problems, Shu and I agreed that it had potential. So we decided to keep working on it – but to shift development over to the yet-to-be-released PS2. This was all done with the understanding that I would become more actively involved in the game’s design and production.

One of the first issues that I had with the game was its combat. We were frustrated with other established combat systems and wanted to radically change how combat could work in a game. We referred to these old systems as “focal attack systems” – where the player was required to aim his character in order to attack. We felt that when the player was required to physically “steer” his character to attack something, it created slow, frustrating battles, and in no way simulated dexterous combat – kind of like doing a three-point turn to hit the guy behind you.

In The Mark of Kri, we aimed for a combat system where the player could hit multiple enemies from all directions with the dexterity and fluidity normally seen in Kung-fu movies. We felt that by removing the need to orientate yourself during combat we would really speed up our game and allow for a dynamic camera.

I pulled some team members into my office one day and showed them Fantavision. I felt we could translate the selection system they used into a fighting game, thus removing the need to physically turn the player. So after a series of long brainstorming sessions, we emerged with an interesting idea of how to handle combat in 3D space. Now we just had to make it work.

Dan Mueller had a long background playing and writing guides for fighting games, such as Tekken. Erik Medina, who is an extremely talented animator, was also a fighting game afficionado (and a mean MK2 player). Rich Karp is an amazing engineer with a deep understanding of what makes games work. These guys worked closely on the problem of making the combat and animation work. What followed was a lot of back and forth between the designers, animators and engineers to manufacture seamless 360 degree combat and a dynamic camera system that complemented the action.

Without this energetic collaboration between design, animation and engineering, the combat — the heart of the game — would not have worked.

The quality of hand animation was an early decision. We wanted the player to look like a badass while playing the game. So the animation, and the crazy kill moves, became very important to the overall experience. Erik, Dan and the team of animators could often be seen acting out the kill moves, sometimes with hilarious consequences.

The team was having fun, and we felt that we were starting to make something fun.

Tim Neveu and I had both worked on Blasto together, where we explored a bold art style. With Mark of Kri we wanted to do something visually fresh, not chase realism like most other games out there.

Tim has a great eye for talent, and had hired Eric Medina and Jeff Merghart for “Barbarian.” They had been monkeying around (Tim’s term) with art styles, and something that was starting to gel was the art direction, a kind of “animated” look – which at the time no one had really done well.

The art style is reminiscent of the painted look people associate with 2D animated feature films, and we studied a good number of these early on in development. We had six animators in total on the game with varied levels of movie experience; these guys injected the life into the characters, but were also responsible for a great many visual and cinematic decisions made in the game.

They brought a simple philosophy to the team: Everything should be done with one thing in mind — entertainment.

We wanted the player to look good at playing the game, and feel good about how he looked when playing it. You know, when someone’s playing a game and his buddies are pushing him to hand over the controller because the game looks that much fun to play. That reaction was our ultimate goal.

As the gameplay and animated violence started to come together, a juxtoposition formed between the gratuitous nature of the combat and the animated art style.

This was the song that we had been looking for…

Shu recognized strengths in the game that others were at times against – such as the art style, and the over-the-top animated violence. He was immediately into the combat system and liked where it was going, but as things started to come together it became apparent that we needed other gameplay mechanics besides hacking and slashing.

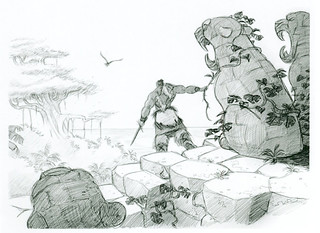

We started to think of each combat scenario as a puzzle, and we gave the player tools that could be used to solve them. Rau had a sword, Taiha, and axe; we then added a bow. Being able to sneak into an enemy camp made more strategic sense than just running in swinging an axe. It also offered an interesting gameplay variant that complemented the frenetic nature of the combat. Making a three hundred pound warrior look stealthy, however, was a monumental challenge – a challenge that our amazing animators were up for. They gave him a bunch of outrageous silent kills, which ended up becoming some of my favorites in the game. The neck break, for example, became a defining moment in the game that everyone loved.

Ok, maybe not everyone. Some wanted to pull stealth out and remove the violence – replacing the blood with sparkles or the like. Shu quickly came to our aid; He saw the potential and supported us all the way. It was clear that he cared first and foremost about quality and pushed to get the best game possible. Frankly, the game would not have been the same without his support.

We continued to think of the game as a puzzle game, or a thinking man’s combat game. We looked for ways to add more tools to support this idea. One was to give Rau a familiar. Initially we talked about giving him a wolf, or a wolverine, but settled instead on a beautiful blackbird.

“Kuzo” came from a need to scout ahead around corners; but he proved to be one of our strongest storytelling tools.

The fiction and world were starting to come together, but Erik and I were growing concerned with how we could deliver all of this information to the player. Cinematics were expensive – one quote came back at nearly a million bucks! We had to come up with an inexpensive and elegant solution to help tell our story.

I had started at SCEA many years before as a concept artist, so I was somewhat familiar with the art software on the market. I had been playing around with Painter and discovered that you could record your brush strokes. I did a quick test, recording myself sketching Rau. I showed it to Tim, Erik and Jeff and suggested that we sketch out our cinematics, and fade into the game. After a couple more tests we got it working (using Jeff’s amazing art). We called these our “bookends,” and used the technique to sketch in or out of the gameplay. They worked, they were inexpensive, and we didn’t need to outsource our cinematics – allowing for greater creative control.

It’s interesting to think that the cinematics were done this way because of financial, time, and creative restrictions, yet ended up being one of the key visual elements in the game. Funny how things work out.

When we started writing the story, I watched Conan back to back a few times – and realized that if the hero rarely speaks, his personality and stoic nature explode off the screen. Conversely, in movies where the warrior archetype chats along merrily, he loses his mystery, his mojo and his strength.

I personally hate wisecracking warriors – so there were no jokes and minimum dialogue for Rau.

Tim, Erik and I talked a great deal about the story. We loved the narration in Conan – how it felt like an epic story was being told. So that’s how I approached writing it: later generations looking back. A grand saga, told by an ancient witness to its events… It was also nice that narration is one of the most flexible ways to craft a story. :)

We always viewed The Mark of Kri as a complete creative experience, and everything we put into the game was placed with purpose, to support its story and its characters.

To us, the music and the voice talent for the game were as creatively critical as any other element. We listened to dozens and dozens of actors before making a choice. We avoided strong “American” accents as they seemed too modern. We also sat in on and directed every line in the game – probably driving our audio team crazy.

When I first started to hear musical samples, I was blown away. It was awe-inspiring. Chuck Doud brought his incredible talents to the team and genuinely cared about how the music matched The Mark of Kri’s mood – rising in tempo as the action picked up, and slowing back down for stealth segments. He worked very hard to get it right, and was key in making it all fit together – without a strong score, games and movies seem lifeless. Chuck made sure that every moment of the game felt alive. Dan is also an accomplished musician, so he and Chuck collaborated to bring many interesting elements into the score, such as Ben Watkins (Juno Reactor), and even some chanting Tibetan monks.

Everyone got involved with focus testing. As the game came together, I watched over 700 hours of gameplay footage – we even made a wall out of videotapes in the office. The team shared a genuine love for this game.

We were proud of what we accomplished, and all the nominations and accolades it received felt great. It’s testament to the game that even after all these years we’re still asked about The Mark of Kri.

Shu was a critical factor in this game coming together – that cannot be understated. He had my back, and allowed us the time to make and correct our mistakes. I have been making games for 24 years, and the development of The Mark of Kri remains one of my happiest, most fulfilling periods, largely in part because of the amazing team that I was lucky enough to work with – wonderfully enthusiastic professionals – but also because of the incredible culture at that time within SCEA.

We had been allowed the time to create an expansive world with language, history, and myth. While designing and creating The Mark of Kri, we also kept in mind where its next chapters might lead. We expanded on the world and fiction in the sequel Rise of the Kasai, but we always felt that the world had many more stories to tell.

Thanks to the Mark of Kri team, everyone involved in developing the game, SCEA, and – of course – Shu.

Related Posts: